How We Learn. Communities Of Practice. The Social Fabric Of A Learning Organization.

You are a claims processor working for a large insurance company. You are good at what you practice, but although you know where your paycheck comes from, the corporation remains mostly an abstraction for you. The group y'all actually work for is a pocket-sized customs of people who share your working conditions. It is with this grouping that you lot learn the intricacies of your chore, explore the meaning of your piece of work, construct an image of the company, and develop a sense of yourself as a worker.

You are an engineer working on ii projects within your business unit. These are demanding projects, and y'all give them your best. Yous respect your teammates and are accountable to your project managers. But when yous confront a problem that stretches your knowledge, you lot plow to people like Jake, Sylvia, and Robert. Even though they work on their own projects in other business organization units, they are your existent colleagues. You lot all go back many years. They understand the problems you confront and volition explore new ideas with yous. And even Julie, who now works for 1 of your suppliers, is just a telephone call away. These are the people with whom you can hash out the latest developments in the field and troubleshoot each other's most difficult design challenges. If merely you had more time for these kinds of interactions.

You are a CEO and, of class, you are responsible for the company every bit a whole. Yous accept care of the "big picture." Only you have to admit that for you, also, the company is mostly an brainchild: names, numbers, processes, strategies, markets, spread-sheets. Sure, you occasionally have tours of the facilities, merely on a solar day-to-day basis, yous live among your peers — your direct reports with whom y'all collaborate in running the company, some lath members, and other executives with whom y'all play golf and talk over a multifariousness of issues.

We frequently say that people are an organization'south virtually important resources. Yet we seldom understand this truism in terms of the communities through which individuals develop and share the capacity to create and employ knowledge. Fifty-fifty when people work for big organizations, they larn through their participation in more specific communities made up of people with whom they collaborate on a regular basis. These "communities of practice" are mostly informal and singled-out from organizational units (see "Communities of Practise" on p. i).

Although we recognize noesis equally a cardinal source of competitive advantage in the business earth, we however have trivial agreement of how to create and leverage information technology in do. Traditional knowledge management approaches attempt to capture existing knowledge within formal systems, such as databases. Yet systematically addressing the kind of dynamic "knowing" that makes a difference in exercise requires the participation of people who are fully engaged in the process of creating, refining, communicating, and using knowledge. Thus, communities of practice are a visitor's near versatile and dynamic noesis resource and form the footing of an organization's ability to know and learn.

COMMUNITIES OF Practice

Defining Communities of Practice

Communities of exercise are everywhere. We all belong to a number of them — at work, at school, at home, in our hobbies. Some take a name; some don't. We are core members of some, and belong to others more peripherally. You may exist a fellow member of a band, or y'all may just come to rehearsals to hang around with the group. You may lead a grouping of consultants who specialize in telecommunication strategies, or you may but stay in touch to keep informed about developments in the field. Or you may have just joined a community and are still trying to find your place in it. Whatever form our participation takes, most of us are familiar with the experience of belonging to a customs of do.

Members of a community are informally bound by what they practise together — from participating in dejeuner-fourth dimension discussions to solving difficult problems—and by what they take learned through their mutual engagement in these activities. A customs of practice is thus different from a community of interest or a geographical community, neither of which implies a shared exercise. A customs of practice defines itself along three dimensions:

- What it is about: its joint enterprise as understood and continually renegotiated by its members

- How information technology functions:the relationships of mutual engagement that bind members together into a social entity

- What capability it has produced: the shared repertoire of communal resources (routines, sensibilities, artifacts, vocabulary, styles, etc.) that members have developed over time.

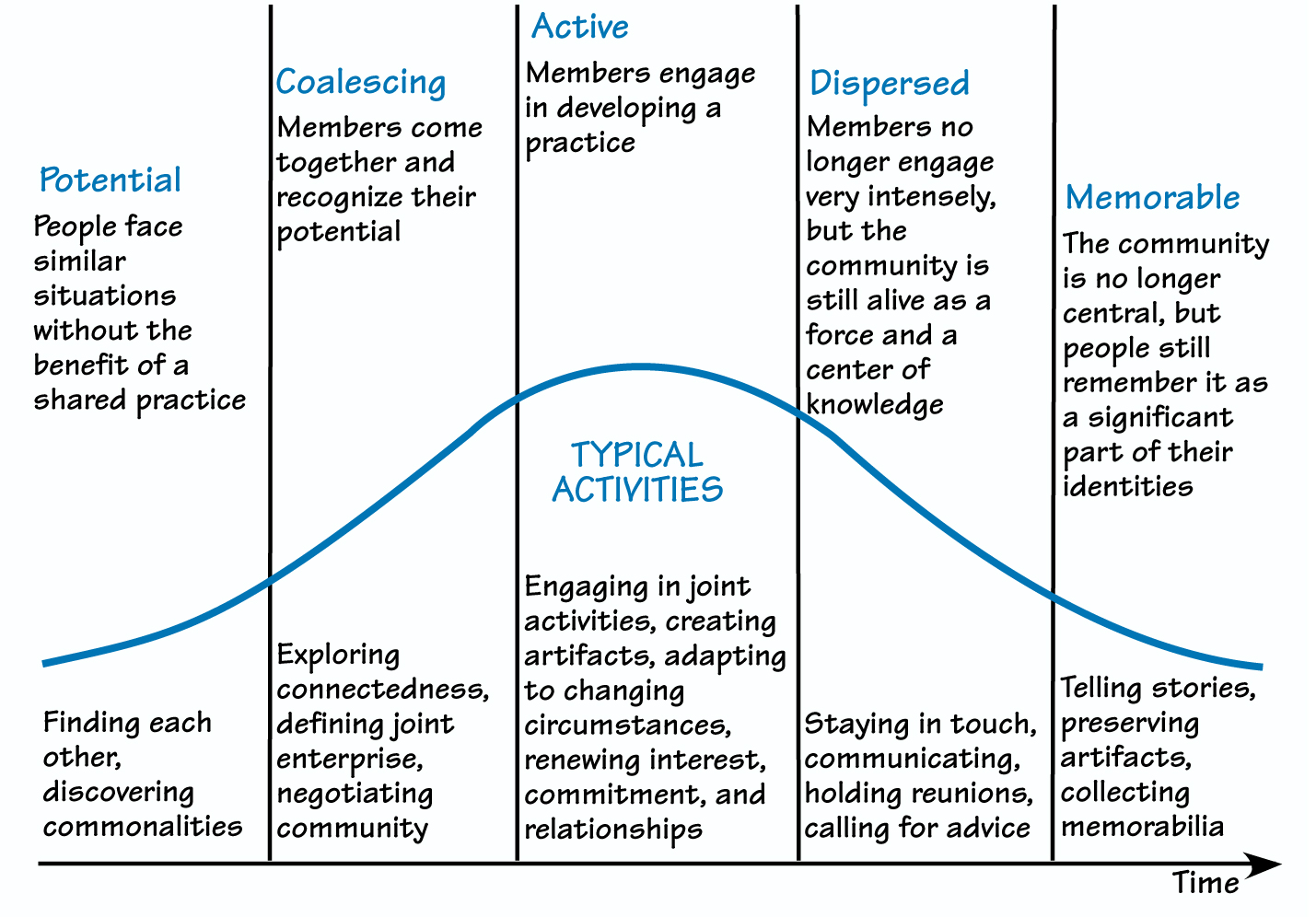

Communities of practice also move through various stages of development characterized past unlike levels of interaction among the members and dissimilar kinds of activities (see "Stages of Evolution" on p. 3).

Communities of practice develop around things that matter to people. As a effect, their practices reverberate the members' own understanding of what is important. Even when a customs's deportment arrange to an external mandate, it is the community — non the mandate — that produces the practice. In this sense, communities of practice are self-organizing systems.

Communities of Practice in Organizations

Communities of practice exist in whatsoever organization. They tin be found:

- Within businesses: Communities of practice arise every bit people address recurring sets of problems together. So, claims processors within an office form communities of practice to deal with the abiding flow of information they need to process. By participating in such a communal retentiveness, they can practice the task without having to call back everything themselves.

- Beyond business units: Of import cognition is often distributed in dissimilar concern units. People who work in cross-functional teams thus course communities of practice to proceed in bear upon with their peers in various parts of the company and maintain their expertise. When communities of practise cutting across business units, they tin develop strategic perspectives that transcend individual product lines. For instance, a customs of practice may propose a plan for equipment purchases that no one business unit of measurement could accept come up up with on its own

- Across company boundaries: In some cases, communities of practice go useful by crossing organizational boundaries. For case, in fast-moving industries, engineers who piece of work for suppliers and buyers alike may form a community of practice to go on up with constant technological changes.Communities of do are non a new kind of organizational unit; rather, they are a dissimilar cut on the organization's structure — ane that emphasizes the learning that people have done together rather than the unit they written report to, the project they are working on, or the people they know. Communities of exercise differ from other kinds of groups constitute in organizations in the fashion they define their enterprise, exist over time, and set their boundaries:

- A community of do is different from a concern or functional unit in that information technology defines itself in the doing, as members develop among themselves their own understanding of what their exercise is about. This living procedure results in a much richer definition than a mere institutional charter. As a consequence, the boundaries of a community of practice are more flexible than those of an organizational unit. The membership involves whoever participates in and contributes to the do. People can participate in different means and to different degrees. This permeable periphery creates many opportunities for learning, as outsiders and newcomers acquire the exercise in concrete terms, and as cadre members proceeds new insights from contacts with less-engaged participants.

- A community of practice is unlike from a team in that the shared learning and interest of its members are what proceed it together. It is defined by knowledge rather than by task, and information technology exists because participation has value to its members. It does non appear the infinitesimal a project is started and does not disappear with the end of a task. It takes a while to come into being and may live long after a projection is completed or an official team has disbanded.

- A community of do is different from a network in the sense that information technology is "nigh" something; it is not simply a prepare of relationships. It has an identity as a community, and thus shapes the identities of its members. A community of practice exists because information technology produces a shared practice every bit members engage in a collective process of learning.People belong to communities of practice at the aforementioned time as they belong to other organizational structures. In their business organisation units, they shape the organization. In their teams, they accept intendance of projects. In their networks, they form relationships. And in their communities of practice, they develop the knowledge that lets them do these other tasks. This informal fabric of communities and shared practices makes the official arrangement effective and, indeed, possible.

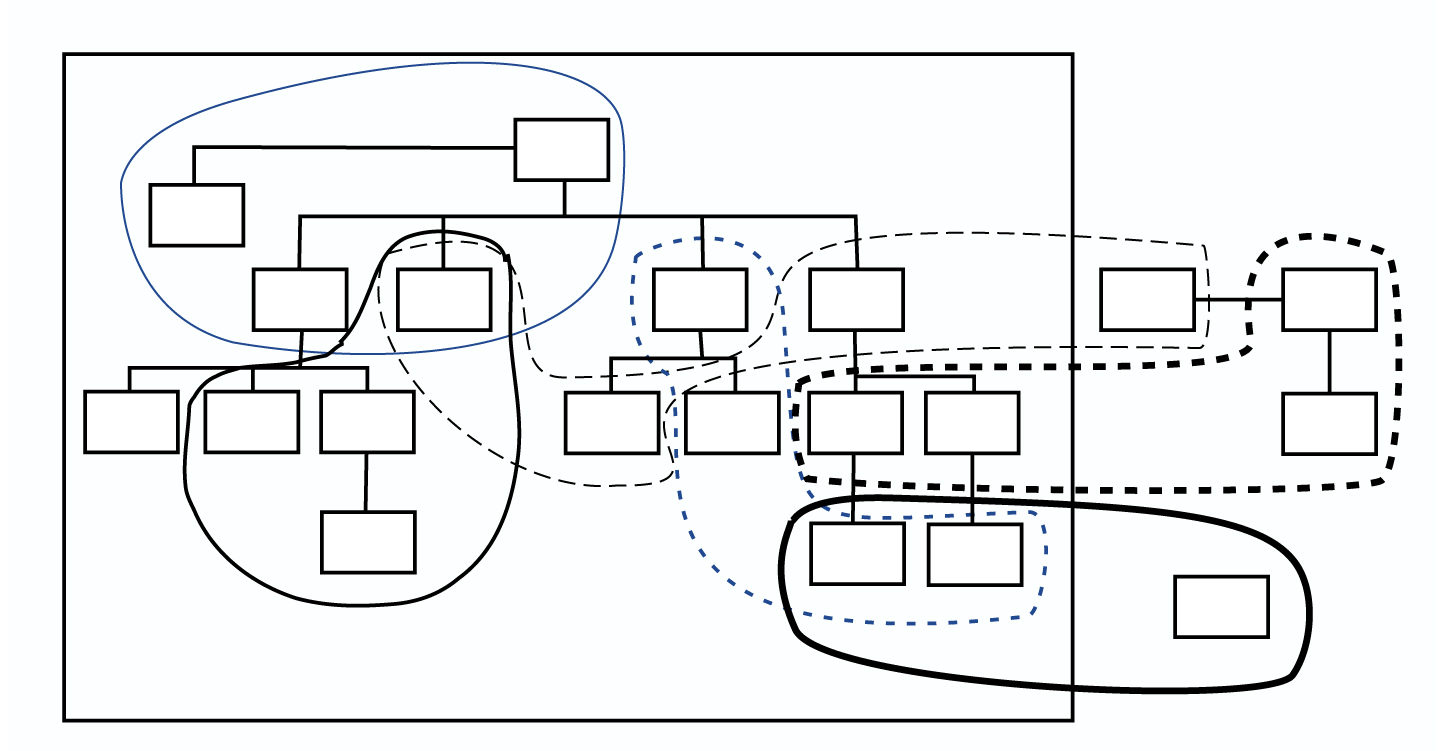

Communities of practice accept different relationships with the official organization. The table "Community'due south Relationship to Official Organization" on p. 4 shows different degrees of institutional involvement, but it does not imply that some relationships are better or more advanced than others. Rather, these distinctions are useful because they draw attending to the issues that tin arise in the interaction between the community of do and the system as a whole.

The Importance to Organizations

Communities of practise are of import to the performance of any system, but they go crucial to those that recognize cognition as a key asset. From this perspective, an effective organization comprises a constellation of interconnected communities of practice, each dealing with specific aspects of the company's competencies — from the peculiarities of a long-standing client, to manufacturing safety, to technical inventions. Knowledge is created, shared, organized, revised, and passed on within and amidst these communities. In a deep sense, it is past these communities that knowledge is "owned" in exercise.

Communities of practice fulfill a number of functions with respect to the creation, accumulation, and diffusion of knowledge in an organisation:

- They are nodes for the exchange and interpretation of information. Because members have a shared agreement, they know what is relevant to communicate and how to present information in useful means. Equally a consequence, a customs of practice that spreads throughout an organization is an ideal channel for moving data — such as best practices, tips, or feedback across organizational boundaries.

- They can retain knowledge in "living" ways, dissimilar a database or a manual. Even when they routinize certain tasks and processes, they can exercise so in a manner that responds to local circumstances and thus is useful to practitioners. Communities of practise preserve the tacit aspects of knowledge that formal systems cannot capture. For this reason, they are platonic for initiating newcomers into a practice.

- They tin can steward competencies to keep the organization at the cutting edge. Members of these groups discuss novel ideas, work together on problems, and continue up with developments within and outside a firm. When a community commits to existence on the forefront of a field, members distribute responsibility for keeping up with or pushing new developments. This collaborative inquiry makes membership valuable, because people invest their professional person identities in beingness role of a dynamic, forrad-looking community

- They provide homes for identities. They are not as temporary as teams, and unlike business units, they are organized around what matters to their members. Identity is important considering, in a bounding main of information, information technology helps u.s.a. sort out what we pay attending to, what nosotros participate in, and what we stay away from. Having a sense of identity is a crucial aspect of learning in organizations. Consider the almanac "computer drop" at a semiconductor company that designs both analog and digital circuits. The computer drib became a ritual by which the analog customs asserted its identity. Once a year, their hero would climb the highest building on the company'southward campus and drop a reckoner, to the neat satisfaction of his peers in the analog gang. The corporate earth is full of these displays of identity, which manifest themselves in the jargon people utilise, the clothes they clothing, and the remarks they brand. If companies want to do good from people's creativity, they must support communities equally a way to help them develop their identities.Communities of practice construction an arrangement's learning potential in two means: through the noesis they develop at their core and through interactions at their boundaries. Like any asset, these communities can become liabilities if their ain expertise becomes insular. It is therefore of import to make sure that there is plenty activity at their boundaries to renew learning. For while the cadre is the heart of expertise, radically new insights oft arise at the boundary. Communities of practise truly go organizational avails when their core and their boundaries are agile in complementary means. To develop the capacity to create and retain knowledge, organizations need to build institutional and technological infrastructures that do non dismiss or impede these communities, but rather recognize, support, and leverage them.

STAGES OF Development

Communities of practice motion through various stages of evolution characterized by different levels of interaction among the members and dissimilar kinds of activities.

Developing and Nurturing Communities of Practice

Just because communities of do arise naturally does non mean that organizations can't practise anything to influence their development. Most communities of practice exist whether or not the system recognizes them. Many are best left lone — some might actually wither under the institutional spotlight. And some may need to be carefully seeded and nurtured. Just a good number volition benefit from some attention, as long every bit this attention does not smother their self-organizing drive.

Whether these communities ascend spontaneously or come together through seeding and nurturing, their evolution ultimately depends on internal leadership. Certainly, in order to legitimize the customs as a place for sharing and creating knowledge, recognized experts need to be involved in some fashion, even if they don't practise much of the work. But internal leadership tin can take many forms:

- The inspirational leadership provided by thought leaders and recognized experts

- The 24-hour interval-to-day leadership provided past those who organize activities

- The classificatory leadership provided by those who collect and organize information in order to certificate practices

- The interpersonal leadership provided by those who weave the social cloth

- The boundary leadership provided past those who connect the community to other communities

- The institutional leadership provided by those who maintain links with other organizational constituencies, in detail the official hierarchy

- The cutting-edge leadership provided by those who pb "out-of-the-box" initiatives

These roles may exist formal or informal, and may be concentrated in a core group or more than widely distributed. But in all cases, leadership must have intrinsic legitimacy in the community. To be constructive, therefore, managers and others must work with communities of practise from the inside rather than merely effort to design them or dispense them from the outside. Nurturing communities of exercise in organizations includes:

Legitimizing Participation. Organizations tin support communities of practice by recognizing the work of sustaining them; by giving members the time to participate in activities; and past creating an environment in which the value they bring is acknowledged. To this cease, information technology is important to have an institutional discourse that includes this dimension of organizational life. Simply introducing the term "communities of do" into an organization'south vocabulary can have a positive effect by giving people an opportunity to talk about how their participation in these groups contributes to the arrangement as a whole.

Negotiating Their Strategic Context.In what Richard McDermott calls "double-knit organizations," people work in teams for projects simply vest to longer-lived communities of exercise for maintaining their expertise. The value of team-based projects that evangelize tangible products is hands recognized, but it is also easy to overlook the potential cost of their curt-term focus. The learning that communities of practice share is simply as disquisitional, but its longer-term value is more subtle to appreciate. Organizations must therefore develop a articulate sense of how knowledge is linked to business concern strategies and utilize this understanding to help communities of exercise clear their strategic value. This involves a process of negotiation that goes both ways. Information technology includes understanding what knowledge — and therefore what practices — a given strategy requires. Conversely, it besides includes paying attention to what emergent communities of practice point with regard to potential strategic directions.

Being Attuned to Real Practices. To be successful, organizations must leverage existing practices. For instance, when the customer service role of a large corporation decided to combine service, sales, and repairs under the same 800 number, researchers from the Constitute for Research on Learning discovered that people were already learning from each other on the job while answering phone calls. IRL so instituted a learning strategy for combining the three functions that took advantage of this existing practice. By leveraging what they were already doing, workers accomplished competency in the three areas much faster than they would have through traditional training. More mostly, the knowledge that companies need is usually already present in some form, and the all-time place to start is to foster the formation of communities of practice that leverage the potential that already exists.

Community'S RELATIONSHIP TO OFFICIAL ORGANIZATION

Fine-tuning the System. Many elements in an organizational environment can foster or inhibit communities of exercise, including management involvement, reward systems, piece of work processes, corporate civilisation, and company policies. These factors rarely determine whether people form communities of practise, only they can facilitate or hinder participation. For case, issues of bounty and recognition often come up. Considering communities of exercise must exist cocky-organizing to learn finer and because participation must be intrinsically self-sustaining, information technology is tricky to use reward systems as a style to manipulate behavior in or micro-manage the community. But organizations shouldn't ignore the consequence of reward and recognition altogether. Rather, they need to arrange reward systems to support participation in learning communities; for instance, past including customs activities and leadership in performance review discussions. Managers also need to make sure that existing compensation systems exercise non inadvertently penalize the work involved in building communities.

Providing Back up.resource, such as exterior experts, travel, meeting facilities, and communications technology. A company-wide squad assigned to nurture community evolution tin help address these needs. This team typically Communities of practice are more often than not self-sufficient, but they can benefit from some

- provides guidance and resources

- helps communities connect their calendar to business concern strategies

- encourages them to move forward and remain focused on the cutting edge

- ensures they include all the correct people

- helps them link to other communities

Such a team can too help identify and eliminate barriers to participation in the structure or culture of the overall organization; for case, conflicts between short-term demands on people's time and the need to participate in learning communities. In addition, simply the existence of such a squad sends the message that the organization values the work and initiative of communities of practice.

The Art of Balancing Design and Emergence

Communities of practice do not usually require heavy institutional infrastructures, but their members do need time and space to collaborate. These communities do not require much management, but they can use leadership. They self-organize, but they flourish when their learning fits with their organizational environment. The art is to help such communities find resources and connections without overwhelming them with organizational meddling. This need for balance reflects the post-obit paradox: No community can fully design the learning of another; but conversely, no customs can fully pattern its own learning.

Acknowledgments:This article reflects ideas and text co-created for presentations with my colleagues Richard McDermott of McDermott & Co., George Por of the Community Intelligence Labs, Beak Snyder of the Social Capital letter Grouping, and Susan Stucky of the Plant for Research on Learning. Thanks to all of them for their personal and intellectual companionship.

Etienne Wenger, PhD, is a globally recognized idea leader in the field of learning theory and its application to business. A pioneer of the "community of do" inquiry and author of Communities of Practice: Learning, Significant, and Identity (Cambridge Academy Press, 1998), he helps organizations employ these ideas through consulting, workshops, and public speaking.

How We Learn. Communities Of Practice. The Social Fabric Of A Learning Organization.,

Source: https://thesystemsthinker.com/communities-of-practice-learning-as-a-social-system/

Posted by: bodenhamerwitheored.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How We Learn. Communities Of Practice. The Social Fabric Of A Learning Organization."

Post a Comment